How Did Native Americans' Service In World War I Impact Their Lives On The Homefront

Weapons for Freedom – United states of americaA. Bonds, Freedom bond affiche by J. C. Leyendecker (1918) | |

| Location | United states |

|---|---|

The United States homefront during World War I saw a systematic mobilization of the country's entire population and economy to produce the soldiers, food supplies, ammunitions and money necessary to win the war. Although the United States entered the state of war in April 1917, there had been very little planning, or fifty-fifty recognition of the issues that Slap-up Britain and the other Allies had to solve on their own home fronts. As a result, the level of confusion was high in the outset 12 months.

The war came in the midst of the Progressive Era, when efficiency and expertise were highly valued. Therefore, both individual states and the federal regime established a multitude of temporary agencies to bring together the expertise necessary to redirect the economic system and social club into the production of munitions and food needed for the war, every bit well as the apportionment of behavior and ideals in order to motivate the people.

American entry into the war [edit]

Firmly maintaining neutrality when World War I began in Europe in 1914, the Usa helped supply the Allies, but could not ship annihilation to Deutschland because of the British blockade. Sympathies among many politically and culturally influential Americans had favored the British cause from the start of the state of war, equally typified by industrialist Samuel Insull, built-in in London, who helped young Americans enlist in British or Canadian forces. On the other paw, particularly in the Midwest, many Irish Americans and High german Americans opposed any American involvement and were anti-British. The suffragist motility included many pacifists, and most churches opposed the war.[1]

German efforts to employ its submarines ("U-boats") to occludent Britain resulted in the deaths of American travelers and sailors, and attacks on passenger liners caused public outrage. Near notable was the torpedoing without warning the passenger liner Lusitania in 1915. Germany promised not to repeat, merely it reversed its position in early on 1917, believing that unrestricted U-boat warfare against all ships headed to Britain would win the war even at the toll of American entry. When Americans read the text of the German offer to Mexico, known as the Zimmermann Telegram, they saw an offer for Mexico to go to war with Frg against the United States, with German funding, with the promise of the return of the lost territories of Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. On April 1, 1917, Wilson called for war, emphasizing that the U.S. had to fight to maintain its honor and to accept a decisive vocalisation in shaping the new postwar earth.[2] Congress voted on Apr vi, 1917 to declare state of war, 82 to vi in the Senate, and 373 to 50 in the House of Representatives.[three]

US government [edit]

Temporary agencies [edit]

Congress authorized President Woodrow Wilson to create a bureaucracy of 500,000 to ane million new jobs in 5 chiliad new federal agencies.[4] To solve the labor crunch, the Employment Service of the Section of Labor attracted workers from the S and Midwest to war industries in the East.

Government propaganda [edit]

In April 1917, the Wilson Administration created the Commission on Public Information (CPI), known as the Creel Commission, to command war information and provide pro-war propaganda. Employing talented writers and scholars, it issued anti-German pamphlets and films. It organized thousands of "4-Minute Men" to deliver brief speeches at flick theaters, schools and churches to promote patriotism and participation in the state of war attempt.[5]

Military draft [edit]

A World War I era draft card.

In 1917 the assistants decided to rely primarily on conscription, rather than voluntary enlistment, to heighten military manpower for World War I. The Selective Service Act of 1917 was advisedly fatigued to remedy the defects in the Civil War arrangement and—past allowing exemptions for dependency, essential occupations, and religious scruples—to place each human being in his proper niche in a national state of war effort. The act established a "liability for military service of all male person citizens"; authorized a selective draft of all those betwixt xx-one and xxx-one years of historic period (afterwards from 18 to forty-five); and prohibited all forms of bounties, substitutions, or buy of exemptions. Assistants was entrusted to local boards equanimous of leading civilians in each community. These boards issued draft calls in order of numbers drawn in a national lottery and determined exemptions. In 1917 and 1918 some 24 meg men were registered and virtually 3 million inducted into the military services, with little of the resistance that characterized the Ceremonious State of war.[vi]

Secretary of War Newton Baker draws the first draft number on twenty July 1917.

Using questionnaires filled out by doughboys as they left the Ground forces, Gutièrrez reports that they were not cynical or disillusioned. They fought "for award, manhood, comrades, and gamble, just especially for duty."[7]

Civil liberties [edit]

The Espionage Human action of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 attempted to punish enemy activity and extended to the penalization expressions of doubt about America'southward role in the war. The Sedition Human action criminalized any expression of opinion that used "disloyal, profane, scurrilous or calumniating linguistic communication" almost the U.S. government, flag or armed forces. Government police activity, private vigilante groups, and public state of war hysteria compromised the civil liberties of many Americans who disagreed with Wilson's policies.[8]

The private American Protective League, working with the Federal Agency of Investigation, was ane of many private patriotic associations that sprang up to support the war and at the aforementioned time identify slackers, spies, draft dodgers and anti-war organizations.[9]

In a July 1917 speech, Max Eastman complained that the government's ambitious prosecutions of dissent meant that "You can't even collect your thoughts without getting arrested for unlawful assemblage."[10]

Motion pictures [edit]

The young film industry produced a wide multifariousness of propaganda films.[11] The most successful was The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin, a "sensational creation" designed to rouse the audience against the German ruler. Comedies included Mutt and Jeff at the Forepart. The greatest artistic success, considered past many a landmark of film history, was Charlie Chaplin's Shoulder Arms, which followed the star from his induction into the military machine, his adventitious penetration of the High german lines, and his eventual return having captured the Kaiser and Crown Prince and won himself a pretty French daughter.[12] Other activities included film shorts supporting the auction of state of war bonds or for state of war relief such as Tom's Footling Star.

One time America entered the war in 1917 Hollywood filmmakers had no more utilize for pop prewar ideological themes of neutrality, pessimism or pacifism. At outset they focused their attending on making heroes out of Wilson and Pershing. Soon they turned the cameras toward portrayals of average Americans facing typical situations; this arroyo resonated better with audiences. The films attacked cowards, and snooty elites who disdained any unsafe gainsay roles in a state of war to purify the world. They reinforced American democracy and attacked hierarchical class structures.[13] By the 1920s and 1930s, however, the mood had reversed and pacifism was shown equally the antidote to the horrors of the Globe War. The blast striking Marx brothers comedy Duck Soup fabricated it clear that stupidity acquired the war. [14] The cycle turned around again by 1941, when Gary Cooper emerged from a religious pacifism to a militant heroism in Sergeant York. Single-handedly he used his backwoods hunting skills to capture an unabridged unit of the highly professional High german regular army.[15]

Economics [edit]

Munitions production before U.S. entry [edit]

By 1916, Britain was funding nearly of the Empire's state of war expenditures, all of Italy's and two thirds of the war costs of France and Russia, plus smaller nations as well. The gold reserves, overseas investments and private credit and then ran out, forcing Britain to borrow $iv billion from the U.S. Treasury in 1917–xviii.[16] Much of this money was spent paying United States industries to manufacture armament. United States Cartridge Company expanded its work force ten-fold in response to September 1914 contracts with British purchasing agents; and ultimately manufactured over 2 billion burglarize and machine gun cartridges.[17] Baldwin Locomotive Works expanded their Eddystone, Pennsylvania, manufacturing facilities in 1915 to manufacture Russian artillery shells and British rifles.[18] The U.s. production of smokeless pulverisation was equal to the combined production of the European Allies during the last nineteen months of the state of war; and by the end of the state of war United States factories were producing smokeless powder at a rate 45 pct higher than the European Allies' combined product. Production rate of explosives past the The states was similarly 40 pct college than Great britain and nearly twice that of France.[xix] Shipments of American raw materials and nutrient allowed Britain to feed itself and its army while maintaining her productivity. The financing was more often than not successful.[20] Heavy investment in ammunition manufacturing machinery did not bring long term prosperity to some major American companies. The United States Cartridge Company Lowell, Massachusetts, manufacturing plant which manufactured almost two-thirds of the small artillery cartridges produced in the United states during the war, closed 8 years later.[21] Afterward Baldwin manufactured over half-dozen 1000000 arms shells, nearly two 1000000 rifles, and v,551 military locomotives for Russian federation, French republic, Britain and the The states,[18] postwar product never used more than ane-third the capacity of the Eddystone manufactory; and Baldwin declared bankruptcy in 1935.[22]

Munitions product afterward U.South. entry [edit]

The Usa endeavour to produce and ship state of war cloth to France was characterized by several factors. The U.s.a. alleged war on Germany on 6 April 1917 with only a small munitions manufacture, very few medium and heavy artillery pieces, and few machine guns. By June 1917 the US had decided that their forces would primarily operate alongside the French, and would acquire their arms and machine guns by purchasing by and large French weapons in theater, along with some British weapons in the case of heavy arms. Shipments from the US to French republic would primarily be of soldiers and armament; artillery equipment in particular occupied besides much infinite and weight to be economic. These priorities combined with the curt 19-calendar month The states participation in the state of war meant that few U.s.a.-made weapons arrived in France, and the need for all-encompassing training of artillery units once in France meant that fewer however saw action earlier the Armistice. A comparison with World War II would exist that the US started preparing for that state of war in earnest shortly after the Germans invaded Poland in September 1939; by the fourth dimension the US entered the war following the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 there had already been 27 months of mobilization.[23]

- Artillery

It was envisioned that US artillery production of French- and British-designed weapons, and a few Us-designed weapons chambered for French armament, would be ramped upwards and that US-made artillery would somewhen be delivered to the battlefields in quantity. However, major production snarls occurred with most of the artillery programs, and as mentioned arms shipments had a lower priority than many other types of shipments overseas.[23]

FWD 'Model B', 3-ton, 4x4 truck

Motor vehicles [edit]

Earlier U.S. entry in WW I, many American-fabricated heavy iv-wheel drive trucks, notably made by Four Wheel Drive (FWD) Automobile Visitor, and Jeffery / Nash Quads, were already serving in foreign militaries, bought by Great Britain, France and Russia. When WW I started, motor vehicles had begun to supercede horses and pulled wagons, but on the European dingy roads and battlefields, two-wheel bulldoze trucks got stuck all the time, and the leading allied countries could non produce 4WD trucks in the numbers they needed.[24] The U.South. Army wanted to supercede four-mule teams used for hauling standard 1 1⁄2 U.S. ton (3000 lb / i.36 metric ton) loads with trucks, and requested proposals from companies in tardily 1912.[25] This led the Thomas B. Jeffery Company to develop a competent four-wheel drive, 1 one⁄2 short ton capacity truck past July 1913: the "Quad".

U.S. Marines riding in a Jeffery Quad, Fort Santo Domingo, c. 1916

The Jeffery Quad, and from the company's take-over past Nash Motors after 1916, the Nash Quad truck, greatly assisted the Earth War I efforts of several Centrolineal nations, particularly the French.[26] The United States Marine Corps first adopted Quads in acrimony in the U.S. occupation of Haiti, and of the Dominican Republic, from 1915 through 1917.[27] The U.Due south. Army's offset heavy usage of Quads was nether general John "Blackjack" Pershing in the 1916 Pancho Villa Expedition in Mexico — both equally regular transport trucks, and in the course of the Jeffery armored motorcar. Once the U.s.A. entered World War I, Nash Quads were used heavily in Pershing's subsequent campaigns in Europe, and they became the workhorse of the Centrolineal Expeditionary Force in that location.[28] [29] Some 11,500 Jeffery / Nash Quads were congenital between 1913 and 1919.[30]

Luella Bates driving a Model B, FWD truck – promotional photo.

The success of the Four Wheel Bulldoze cars in early on military tests had prompted the company to switch from cars to truck manufacturing. In 1916 the U.S. Army ordered 147 FWD Model B, 3-ton (6000 lb / 2700 kg) capacity trucks for the United mexican states border Trek,[31] and later on ordered an amount of 15,000 FWD Model B 3-ton trucks as the "Truck, 3 ton, Model 1917" during World State of war I, with over 14,000 actually delivered. Boosted orders came from the United kingdom and Russia.[32] Once the FWD and Jeffery / Nash 4-wheel drive trucks were required in large numbers in World War I, both models were built under license by several additional companies to meet demand. The FWD Model B was produced under license by 4 additional manufacturers.[31]

The Quad and the FWD trucks were the globe's first four-wheel drive vehicles to be made in five-effigy numbers, and they incorporated many authentication technological innovations, that as well enabled the decisive U.Due south. and Allied usage of 4x4 and 6x6 trucks in Globe War Two. The Quad's production continued for 15 years with a total of 41,674 units fabricated.[33]

Socially, it was the FWD company that employed Luella Bates, believed to exist the beginning female truck commuter, chosen to work as test and sit-in driver for FWD, from 1918 to 1922.[34] [35] During Globe War I, she was a test driver traveling throughout the state of Wisconsin in an FWD Model B truck. After the state of war, when the majority of the women working at Four Wheel Drive were permit go, she remained every bit a demonstrator and driver.[34]

Farming and nutrient [edit]

Food Assistants poster 1917

The nutrient programme was a major success, as output expanded, waste was reduced, and both the home front and the Allies received more food.[36] The U.S. Food Assistants nether Herbert Hoover launched a massive campaign to teach Americans to economize on their food budgets and abound victory gardens in their backyards.[37] It managed the nation's food distribution and prices.[38]

Gross farm income increased more than than 230% from 1914 to 1919. Apart from 'wheatless Wednesdays' and 'meatless Tuesdays' due to poor harvests in 1916 and 1917, at that place were 'fuelless Mondays' and 'gasless Sundays' to preserve coal and gasoline.[39]

Economic confusion in 1917 [edit]

In terms of munitions production, the kickoff xv months involved an amazing parade of mistakes, misguided enthusiasm, and defoliation.[twoscore] Americans were willing enough, but they did not know their proper role. Washington was unable to figure out what to do when, or even to determine who was in charge. Typical of the confusion was the coal shortage that hitting in December 1917. Because coal was by far the major source of energy and oestrus a grave crisis ensued. There was in fact enough of coal being mined, just 44,000 loaded freight and coal cars were tied up in horrendous traffic jams in the runway yards of the Due east Coast. Two hundred ships were waiting in New York harbor for cargo that was delayed by the mess. The solution included nationalizing the coal mines and the railroads for the duration, shutting down factories one day a week to save fuel, and enforcing a strict arrangement of priorities. Only in March, 1918, did Washington finally accept control of the crisis[41] The transportation organization then worked smoothly.[42]

Shipments to Europe [edit]

Shipbuilding became a major wartime industry, focused on merchant ships and tankers.[43] Merchant ships were often sunk until the convoy system was adopted using British and Canadian naval escorts. Convoys were irksome but effective in stopping u-boat attacks.[44] The troops were shipped over on fast passenger liners that could easily outrun submarines.[45]

An oil crunch occurred in Great britain due to the 1917 German language submarine campaign. Standard Oil of NJ, for case, lost 6 tankers (including the brand new "John D. Archbold") betwixt May and September. The solution was expanded oil shipments from America in convoys. The Allies formed the Inter-Centrolineal Petroleum Conference with USA, Britain, France, and Italy every bit the members. Standard and Regal Dutch/Shell ran it and made it work. The introduction of convoys every bit an antidote to the German U-boats and the joint management organisation by Standard Oil and Royal Dutch/Shell helped to solve the Allies' supply problems. The shut working relationship that evolved was in marked contrast to the feud between the government and Standard Oil years before. In 1917 and 1918, there was increased domestic demand for oil partly due to the cold winter that created a shortage of coal. Inventories and imported oil from Mexico were used to shut the gap. In Jan 1918, the U.S. Fuel Administrator ordered industrial plants east of Mississippi to close for a week to free upwardly oil for Europe.[46]

The coal shortage caused sharp increases in the need and prices of oil and industry called for voluntary price control from the oil manufacture. While Standard Oil was amusing, the independent oil companies were non. Demand continued to outpace supply because of the war and the growth in automobiles in America. An appeal for "Gasolineless Sundays" in United states of america was made with exceptions for freight, doctors, police, emergency vehicles, and funeral cars.

Labor [edit]

1919 New York Herald cartoon portraying "reds" and IWW members as a vehement mob held back past threat of a US Regular army machine gun

The American Federation of Labor (AFL) and affiliated merchandise unions were potent supporters of the war effort. Fear of disruptions to war production by labor radicals provided the AFL political leverage to proceeds recognition and mediation of labor disputes, oft in favor of improvements for workers.[47] They resisted strikes in favor of arbitration and wartime policy, and wages soared every bit near-full employment was reached at the height of the state of war. The AFL unions strongly encouraged immature men to enlist in the military, and fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and dull state of war production by pacifists, the anti-war Industrial Workers of the Globe (IWW) and radical socialists. To keep factories running smoothly, Wilson established the National War Labor Board in 1918, which forced management to negotiate with existing unions.[48] Wilson too appointed AFL president Samuel Gompers to the powerful Council of National Defence force, where he fix the War Committee on Labor.

Subsequently initially resisting taking a stance, the IWW became actively anti-war, engaging in strikes and speeches and suffering both legal and illegal suppression by federal and local governments as well as pro-war vigilantes. The IWW was branded equally anarchic, socialist, unpatriotic, alien and funded by German language aureate, and violent attacks on members and offices would go on into the 1920s.[49]

The AFL membership soared to 2.iv million in 1917. In 1919, the AFL tried to make their gains permanent and called a serial of major strikes in meat, steel and other industries. The strikes ultimately failed, forcing unions back to membership and power similar to those around 1910.[fifty]

[edit]

African-Americans [edit]

With an enormous need for expansion of the defense industries, the new draft police force in effect, and the cutting off of immigration from Europe, demand was very high for underemployed farmers from the S. Hundreds of thousands of African-Americans took the trains to Northern industrial centers. Migrants going to Pittsburgh and surrounding mill towns in western Pennsylvania between 1890 and 1930 faced racial bigotry and limited economic opportunities. The black population in Pittsburgh jumped from half dozen,000 in 1880 to 27,000 in 1910. Many took highly paid, skilled jobs in the steel mills. Pittsburgh'due south blackness population increased to 37,700 in 1920 (vi.4% of the total) while the black element in Homestead, Rankin, Braddock, and others nearly doubled. They succeeded in edifice effective community responses that enabled the survival of new communities.[51] [52] Historian Joe Trotter explains the decision process:

- Although African-Americans ofttimes expressed their views of the Swell Migration in biblical terms and received encouragement from northern black newspapers, railroad companies, and industrial labor agents, they also drew upon family and friendship networks to assistance in the movement to Western Pennsylvania. They formed migration clubs, pooled their money, bought tickets at reduced rates, and often moved ingroups. Earlier they made the decision to move, they gathered information and debated the pros and cons of the process....In barbershops, poolrooms, and grocery stores, in churches, club halls, and clubhouses, and in private homes, southern blacks discussed, debated, and decided what was expert and what was bad about moving to the urban North.[53]

After the war ended and the soldiers returned home, tensions were very high, with serious labor spousal relationship strikes involving black strikebreakers and inter-racial riots in major cities. The summer of 1919 was the Cherry Summer with outbreaks of racial violence killing about ane,000 people beyond the nation, most of whom were black.[54] [55]

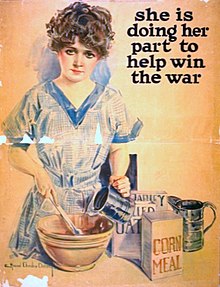

Women [edit]

During WWI (1914-1918), large numbers of women were recruited into jobs that had either been vacated by men who had gone to fight in the war, or had been created as part of the war effort. The high need for weapons and the overall wartime situation resulted in munitions factories collectively becoming the largest employer of American women past 1918. While there was initial resistance to hiring women for jobs traditionally held past men, the war made the need for labor so urgent that women were hired in large numbers and the government fifty-fifty actively promoted the employment of women in war-related industries through recruitment drives. As a outcome, women non just began working in heavy industry, just also took other jobs traditionally reserved solely for men, such as railway guards, ticket collectors, bus and tram conductors, postal workers, police officers, firefighters, and clerks.

Mary Van Kleeck led the Department of Labor attempt to set employment standards for working women during the war

World War I saw women taking traditionally men'south jobs in large numbers for the first time in American history. Many women worked on the assembly lines of factories, producing trucks and munitions, while department stores employed African American women equally lift operators and cafeteria waitresses for the showtime time. The Nutrient Administration helped housewives prepare more nutritious meals with less waste and with optimum utilise of the foods available. Most important, the morale of the women remained loftier, as millions joined the Cerise Cross as volunteers to help soldiers and their families, and with rare exceptions, the women did non protest the draft.[56] [57]

The Department of Labor created a Women in Industry group, headed past prominent labor researcher and social scientist Mary van Kleeck.[58] This group helped develop standards for women who were working in industries connected to the war alongside the War Labor Policies Board, of which van Kleeck was as well a member. Later the war, the Women in Industry Service group adult into the U.S. Women'southward Agency, headed past Mary Anderson.[58] [59]

Girls too immature for paid jobs learned how they could assistance the war effort.

Children [edit]

Earth War I afflicted children in the United States through several social and economic changes in the schoolhouse curriculum and through shifts in parental relationships. For case, a number of fathers and brothers entered the war, and many were later on maimed in action or killed, causing many children to exist brought up by single mothers.[60] Additionally, as the male workforce left for battle, mothers and sisters began working in factories to take their positions, and the family dynamic began to alter; this affected children as they had less time to spend with family members and were expected to grow upwardly faster and help with the state of war endeavor. Similarly, Woodrow Wilson called on children involved in youth organizations to assistance collect money for war bonds and stamps in gild to raise money for the war effort.[61] This was very of import because the children were having a straight effect on the financial country of the United States government during Earth War I. As children were collecting large amounts of money outside of school, within the classroom, curriculum also began to alter every bit a outcome of the state of war. Woodrow Wilson again became involved with these children every bit he implemented government pamphlets and programs to encourage state of war support through things like mandatory patriotism and nationalism classes multiple times a week.[62] Fifty-fifty though war was not being fought on United States soil, children's lives were greatly afflicted equally all of these changes were fabricated to their daily lives equally a result of the conflict.

Americanization of people with dissimilar ethnicities [edit]

The outbreak of war in 1914 increased business organisation well-nigh the millions of foreign born in the Us. The short-term business organization was their loyalty to their native countries and the long-term was their assimilation into American society. Numerous agencies became active in promoting "Americanization" and so that people of differing ethnicities would be psychologically and politically loyal to the U.Southward. The states prepare programs through their Councils of National Defense; numerous federal agencies were involved, including the Agency of Education, the United States Department of the Interior and the Food Administration. The most of import individual organization was the National Americanization Committee (NAC) directed by Frances Kellor. 2d in importance was the Committee for Immigrants in America, which helped fund the Division of Immigrant Education in the federal Bureau of Education.[63]

The state of war prevented millions of recently arrived immigrants from returning to Europe every bit they originally intended. The nifty majority decided to stay in America. Strange language use declined dramatically. They welcomed Americanization, frequently signing upwards for English classes and using their savings to buy homes and bring over other family members.[64]

Kellor, speaking for the NAC in 1916, proposed to combine efficiency and patriotism in her Americanization programs. It would be more efficient, she argued, in one case the factory workers could all understand English and therefore better understand orders and avoid accidents. Once Americanized, they would grasp American industrial ideals and be open to American influences and not field of study only to strike agitators or foreign propagandists. The consequence, she argued would transform indifferent and ignorant residents into agreement voters, to make their homes into American homes, and to establish American standards of living throughout communities of various ethnicities. Ultimately, she argued information technology would "unite foreign-born and native alike in enthusiastic loyalty to our national ideals of liberty and justice.[65]

Conflicting internments [edit]

German language citizens were required to register with the federal government and acquit their registration cards at all times. ii,048 German citizens were imprisoned beginning in 1917, and all were released by spring 1920. Allegations against them included spying for Federal republic of germany or endorsing the German war effort. They ranged from immigrants suspected of sympathy for their native land, civilian German sailors on merchant ships in U.South. ports when war was declared, and Germans who worked part of the year in the United States, including 29 players from the Boston Symphony Orchestra and other prominent musicians.[66]

Anti-German activity [edit]

1918 bond posters with germanophobic slogans

German Americans past this fourth dimension usually had but weak ties to Germany; still, they were fearful of negative treatment they might receive if the U.s. entered the war (such mistreatment was already happening to German-descent citizens in Canada and Commonwealth of australia). Almost none called for intervening on Germany'southward side, instead calling for neutrality and speaking of the superiority of German culture. They were increasingly marginalized, still, and by 1917 had been excluded well-nigh entirely from national discourse on the subject area.[67]

When the war began, overt examples of German language culture came under set on. Many churches cut back or concluded their German services. German parochial schools switched to the utilize of English language in the classroom. Courses in German language were dropped from public loftier school curricula. Some street names were changed. One person was killed by a mob at a tavern in a southern Illinois mining boondocks.[68]

War bonds [edit]

Elaborate propaganda campaigns were launched to encourage Americans to buy Liberty bonds. In indigenous centers, ethnic groups were pitted against each other so that groups were encouraged to purchase more bonds compared to their historic rivals in order to demonstrate superior patriotism.[69] [70] [71]

Attacks on the U.Due south. [edit]

The Central Powers carried out a number of acts of demolition and a unmarried submarine attack confronting the U.S. while being neutral and belligerent with the country during the war, but never staged an invasion, although in that location were rumors that High german advisers were nowadays at the Battle of Ambos Nogales.

Sabotage [edit]

Black Tom Pier shortly afterwards the explosion.

Numerous rumors of German plans for sabotage alarmed Americans. Later midnight on July 30, 1916, a serial of small fires were found on a pier in Jersey City, New Bailiwick of jersey. Sabotage was suspected and some guards fled, fearing an explosion; others attempted to fight the fires. Eventually, they called the Jersey City Burn down Section. An explosion occurred at ii:08 a.1000., the first and biggest of the explosions. Shrapnel from the explosion traveled long distances, some lodging in the Statue of Liberty and other places. Half dozen months later, on xi Jan 1917, German agents ready fire at an armament assembly constitute near Lyndhurst, New Jersey, causing a four-hour fire that destroyed half a million 3-inch explosive shells and destroyed the plant for an estimated at $17 million in damages.

On July 21, 1918, a German U-gunkhole, SMU-156, positioned itself off of Orleans, Massachusetts and opened fire and sank a tugboat and some barges until information technology was driven off past American warplanes.

See too [edit]

- American entry into World State of war I

- Victory garden

- Adult female'south Land Army of America

- Effect of World War I on Children in the U.s.a.

- United states abode front during World War II

- German prisoners of war in the Us

- Domicile front during World State of war I, covering all major countries involved

- Women'southward roles in the World Wars#World War I

- British dwelling house front end during the Offset World War

- History of Deutschland during Earth War I

- History of France during World War I

- Kingdom of belgium in Earth War I

Notes and references [edit]

- ^ On the historiography, come across Justus D. Doenecke, "Neutrality Policy and the Decision for State of war" in Ross Kennedy ed., A Companion to Woodrow Wilson (2013) pp: 243-69 Online

- ^ For detailed coverage of Wilson's speech meet NY Times main headline, April 2, 1917, President Calls for State of war Declaration, Stronger Navy, New Army of 500,000 Men, Full Cooperation With Federal republic of germany's Foes

- ^ Staff, History.com. "U.Southward. Entry into Earth War I." History.com, A&E Television Networks, 2017, www.history.com/topics/earth-state of war-i/u-s-entry-into-earth-war-i.

- ^ Spencer Tucker and Priscilla Mary Roberts, eds., World War I: encyclopedia (2005), p. 1205

- ^ Kennedy, Over Here, 61-62

- ^ John Whiteclay Chambers Ii, To Heighten an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987)

- ^ Edward A. :Gutièrrez, Doughboys on the Dandy War: How American Soldiers Viewed Their Military Experience (2014)

- ^ Schaffer, Ronald (1978). The The states in Globe State of war I . Santa Barbara: Clio Books. p. ?. ISBN0874362741.

- ^ Fischer, Nick (2011). "The American Protective League and the Australian Protective League – Two Responses to the Threat of Communism, c. 1917–1920". American Communist History. 10 (2): 133–149. doi:ten.1080/14743892.2011.597222. S2CID 159532719.

- ^ Steel, Ronald (1980). Walter Lippmann and the American Century . Boston: Little, Brown. p. 124. ISBN0316811904.

- ^ For archival holdings see "WWI Films at the National Athenaeum in College Park, Dr."

- ^ Mock, James R.; Larson, Cedric (1939). Words that Won the War: The Story of the Committee on Public Information, 1917–1919. Princeton Academy Press. pp. 151–152.

- ^ Michael T. Isenberg, "The mirror of republic: reflections of the war films of Globe War I, 1917-1919," Journal of Pop Civilization (1976) 9#4 pp 878-885.

- ^ Michael T. Isenberg, "An Ambiguous Pacifism: A Retrospective on World War I Films, 1930-1938." Journal of Pop Film four.two (1975): 98-115.

- ^ Michael Due east. Birdwell, "A Change of Heart: Alvin York and the Movie Sergeant York." Film & History 27.i (1997): 22-33.

- ^ Steven Lobell, "The Political Economy of State of war Mobilization: From United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland's Limited Liability to a Continental Delivery," International Politics (2006) 43#3 pp 283–304

- ^ Engelbrecht, Helmuth Carol; Hanighen, Frank Cleary (1934). Merchants of Death: A Study of the International Ammunition Manufacture. p. 187. ISBN9781610163903.

- ^ a b Westing, Frederick (1966), The locomotives that Baldwin built. Containing a complete facsimile of the original "History of the Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1923", Crown Publishing Group, pp. 76–85, ISBN978-0-517-36167-2

- ^ Ayres, Leonard P. (1919). The War with Germany (Second ed.). Washington, DC: United States Government Printing Office. pp. 77&78.

- ^ M. J. Daunton, "How to Pay for the State of war: State, Gild and Revenue enhancement in Uk, 1917–24," English Historical Review (1996) 111# 443 pp. 882–919 in JSTOR

- ^ "U.S. Cartridge Company" (PDF). Lowell State Trust. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-04-26. Retrieved 2013-02-06 .

- ^ Brown, John G. (1995), The Baldwin Locomotive Works, 1831-1915: A Report in American Industrial Practice, Studies in Industry and Lodge series, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 216&228, ISBN978-0-8018-5047-9

- ^ a b Crowell, pp. 25-30

- ^ produced by UAW and Jeep (27 September 2007). Jeep: Steel Soldier (documentary). "Toledo Stories": PBS. Result occurs at 2:08–2:51 min. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 2020-10-21 .

- ^ Adolphus, David Traver (August 2011). "Where none could possibly travel Jeffery's Quads became the backbone of both commerce and state of war". Hemmings Classic Automobile . Retrieved 4 March 2018.

- ^ Shrapnell-Smith, Edmund (1915). Our Despatches from the Front: Huge Deliveries of Lorries for the French Government. Drivers for Quads. American Tire Sizes, in The Commercial Motor. Temple Press (since 2011, Road Transport Media). p. 229. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Buckner, David Due north. (1981). Marine Corps Historical Partition (ed.). A Brief History of the 10th Marines (PDF). Washington D.C.: United states of america Marine Corps. 19000308400. Retrieved three March 2018.

- ^ Hyde, Charles (2009). The Thomas B. Jeffery Company, 1902-1916, in Storied Independent Automakers. Wayne State University Printing. pp. 1–twenty. ISBN978-0-8143-3446-1 . Retrieved 6 Dec 2014.

- ^ "Charles Thomas Jeffery". The Lusitania Resource. 25 July 2011. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ Mroz, Albert (2009). American Military Vehicles of Earth War I: An Illustrated History of Armored Cars, Staff Cars, Motorcycles, Ambulances, Trucks, Tractors and Tanks . McFarland. p. xix. ISBN978-0-7864-3960-vii.

- ^ a b Karolevitz, Robert (1966). This Was Trucking: A Pictorial History of the start quarter century of the trucking industry . Seattle: Superior Publishing Company. p. 100. ISBN0-87564-524-0.

- ^ "FWD Model B". Military machine Manufactory. Military Factory. Retrieved March 4, 2018.

- ^ Redgap, Curtis; Watson, Beak (2010). "The Jefferys Quad and Nash Quad — 4x4 Ancestor to the Willys Jeep". Allpar. Retrieved 6 December 2014.

- ^ a b "Can a Daughter Be Every bit Good a Mechanic As a Homo Is Question". Monongahela Pennsylvania Daily Republican. June thirty, 1920 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Karolevitz (1966), page 43.

- ^ Beamish and March (1919). America's Part in the World War. pp. 319–35.

- ^ "Education With Documents: Sow the Seeds of Victory! Posters from the Food Assistants During Globe State of war I"

- ^ Nash, George H. (1996). The Life of Herbert Hoover: Master of Emergencies, 1917–1918. New York: Norton. p. ?. ISBN0393038416.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C.; Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). Encyclopedia Of Globe War I: A Political, Social, And Military History. ABC-CLIO. p. 1206. ISBN9781851094202.

- ^ Allan R. Millett and Peter Maslowski, For the Mutual Defense (1994) pp 352–353.

- ^ Kennedy, Over Here 113-25

- ^ Beamish and March (1919). America's Role in the Earth War. pp. 336–50.

- ^ Beamish and March (1919). America's Part in the Globe War. pp. 359–66.

- ^ Brian Tennyson, and Roger Sarty. "Sydney, Nova Scotia and the U-Gunkhole War, 1918." Canadian Military History 7.one (2012): 4+ online

- ^ Holger H. Herwig, and David F. David. "The Failure of Purple Germany's Undersea Offensive Against World Shipping, February 1917–October 1918." Historian (1971) 33#4 pp: 611-636.

- ^ Ferrier, Ronald W.; Bamberg, J. H. (1982). The History of the British Petroleum Visitor: Volume 1, The Developing Years, 1901-1932. Cambridge University Printing. p. 356. ISBN9780521246477.

- ^ Joseph A. McCartin, Labor'south great war: the struggle for industrial republic and the origins of modern American labor relations, 1912-1921 (1997).

- ^ Richard B. Gregg, "The National War Labor Board." Harvard Law Review (1919): 39-63 in JSTOR

- ^ Robert L. Tyler, Rebels of the wood: the IWW in the Pacific Northwest (U of Oregon Press, 1967)

- ^ Philip Taft, The A.F.L. in the fourth dimension of Gompers (1957)

- ^ Joe W. Trotter, "Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania." Western Pennsylvania History (1995) 78#4: 153-158 online.

- ^ Joe W. Trotter, and Eric Ledell Smith, eds. African Americans in Pennsylvania: Shifting Historical Perspectives (Penn State Press, 2010).

- ^ Trotter, "Reflections on the Great Migration to Western Pennsylvania," p 154.

- ^ Jam Voogd, Race Riots & Resistance: The Red Summer of 1919 (Peter Lang, 2008).

- ^ David F. Krugler, 1919, The Yr of Racial Violence (Cambridge Upward, 2014).

- ^ Gavin, Lettie (2006). American Women in World War I: They Also Served. Boulder: Academy Printing of Colorado. ISBN0870818252.

- ^ Beamish and March (1919). America's Part in the Globe War. pp. 259–72.

- ^ a b "Biographical/Historical - Mary van Kleeck". findingaids.smith.edu. Smith College Special Collections. Retrieved 2019-09-05 .

- ^ "United States Women's Bureau | United states of america federal agency". Encyclopedia Britannica . Retrieved 2019-09-05 .

- ^ Greenwald, Maureen (1980). Maurine Weiner. Women, War, and Work: the Impact of Globe War I on Women Workers in the U.s. . Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 4. ISBN0313213550.

- ^ McDermott, T. P. "Us'due south Boy Scouts and World War I Freedom Loan Bonds". SOSSI Journal: 70.

- ^ Spring, Joel (1992). Images of American Life. Albany: State Academy of New York Press. p. 20. ISBN0791410692.

- ^ McClymer, John F. (1980). State of war and Welfare: Social Applied science in America, 1890–1925 . Westport: Greenwood Press. pp. 110–111. ISBN0313211299.

- ^ Archdeacon, Thomas J. (1984). Becoming American . London: Collier Macmillan. pp. 115, 186–187. ISBN0029008301.

- ^ McClymer, War and Welfare, pp 112-3

- ^ New York Times: "Dr. Muck Bitter at Sailing," August 22, 1919, accessed January 13, 2010

- ^ Frederick C. Luebke, Bonds of Loyalty: High german-Americans and Globe War I (1974)

- ^ Donald R. Hickey, "The Prager Thing: A Study in Wartime Hysteria," Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1969) 62#2 pp 126–127 in JSTOR

- ^ Alexander, June (2008). Ethnic Pride, American Patriotism: Slovaks And Other New Imiigrants. Temple UP. pp. 33–34. ISBN9781592137800.

- ^ Sung Won Kang and Hugh Rockoff. "Capitalizing patriotism: the Freedom loans of World War I." Fiscal History Review 22.1 (2015): 45+ online

- ^ For full coverage see Charles Gilbert, American financing of Earth War I (1970) online

Further reading [edit]

- Beamish, Richard Joseph; March, Francis Andrew (1919). America's Part in the World War: A History of the Full Greatness of Our Country'due south Achievements; the Record of the Mobilization and Triumph of the Military, Naval, Industrial and Civilian Resources of the U.s.a.. Philadelphia: John C. Winston Company. ; comprehensive history of military and dwelling house front; total text online; has photos

- Breen, William J. Uncle Sam at Home: Civilian Mobilization, Wartime Federalism, and the Quango of National Defence force, 1917-1919 (Greenwood Press, 1984)

- Chambers, John W., 2. To Raise an Regular army: The Draft Comes to Mod America (1987) online

- Clements, Kendrick A. The Presidency of Woodrow Wilson (1992) nline

- Cooper, John Milton. Woodrow Wilson: A Biography (2009) online

- Crowell, Benedict (1919). America's Munitions 1917-1918. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

- Dumenil, Lynn. The Second Line of Defense force: American Women and World War I (U of Due north Carolina Press, 2017). xvi, 340 pp.

- Encyclopædia Britannica (12th ed. 1922) comprises the 11th edition plus iii new volumes 30-31-32 that cover events since 1911 with very thorough coverage of the war too as every country and colony. Included also in 13th edition (1926) partly online

- full text of vol 30 ABBE to ENGLISH HISTORY online gratuitous

- Gannon, Barbara A. "The Groovy State of war and Modern Amnesia: Studying Pennsylvania's Smashing War, Part 2' Pennsylvania History (2017) 84#iii:287-91 Online

- Garrigues, George. Liberty Bonds and Bayonets, (Urban center Desk Publishing, 2020), the home front in St. Louis, Missouri ISBN 978-1651488423

- Hamilton, John M. Manipulating the Masses: Woodrow Wilson and the Nascency of American Propaganda. (Louisiana State University Press, 2020) online review

- Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The Showtime Globe War and American Order (2004), comprehensive coverage infringe for fourteen days

- Link, Arthur Stanley. Woodrow Wilson and the Progressive Era, 1910–1917 (1972) standard political history of the era borrow for fourteen days

- Link, Arthur Stanley. Wilson: The Struggle for Neutrality: 1914–1915 (1960); Wilson: Confusions and Crises: 1915–1916 (1964); Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916–1917 (1965), the standard biography to 1918

- Malin, James C. The United States after the World War (1930) online [ dead link ]

- Meyer G.J. The Earth Remade: America In World War I (2017), popular survey, 672pp

- North, Diane M.T. California at State of war: The State and the People during World War I (2018) online review

- Paxson, Frederic L. Pre-state of war years, 1913-1917 (1936) wide-ranging scholarly survey

- Paxson, Frederic L. American at State of war 1917-1918 (1939) wide-ranging scholarly survey

- Philadelphia War History Committee (1922). Philadelphia in the World War, 1914-1919. full text online

- Schaffer, Ronald. America in the Great War: The Rising of the State of war-Welfare State (Oxford University Press, 1991), ISBN 0-xix-504904-7

- Startt, James D.. Woodrow Wilson, the Great State of war, and the Fourth Estate (2017) online review

- Titus, James, ed. The Home Front and War in the Twentieth Century: The American Experience in Comparative Perspective (1984) essays past scholars. online free

- Tucker, Spencer C., and Priscilla Mary Roberts, eds. The Encyclopedia of World War I : A Political, Social, and Military History (5 vol. 2005)

- Vaughn, Stephen. Belongings Fast the Inner Lines: Democracy, Nationalism, and the Commission on Public Information (1980) online

- Venzon, Anne ed. The Us in the Kickoff Globe War: An Encyclopedia (1995), Very thorough coverage.

- Williams, William John. The Wilson administration and the shipbuilding crisis of 1917: steel ships and wooden steamers (1992).

- Wilson, Ross J. New York and the Offset Earth War: Shaping an American City (2014).

- Young, Ernest William. The Wilson Assistants and the Great War (1922) online edition

- Zieger, Robert H. America'south Cracking War: World State of war I and the American Experience 2000. 272 pp.

Economics and labor [edit]

- Gage, Robert D. The war industries board: Business organization-government relations during World War I (1973).

- Gage, Robert D. "The politics of labor assistants during world war I." Labor History 21.iv (1980): 546–569.

- Dubofsky, Melvyn. "Abortive reform: the Wilson administration and organized labor, 1913-1920." in Work, Community, and Power: The Experience of Labor in Europe and America, 1900-1925 edited by James E. Cronin and Sirianni, (1983): 197–220.

- Haig, Robert Murray. "The Revenue Deed of 1918," Political Science Quarterly 34#3 (1919): 369–391. in JSTOR

- Kester, Randall B. "The War Industries Board, 1917–1918; A Study in Industrial Mobilization," American Political Science Review 34#4 (1940), pp. 655–84; in JSTOR

- Myers, Margaret Thou. Financial History of the United States (1970). pp 270–92. online

- Rockoff, Hugh. "Until it's Over, Over In that location: The U.S. Economy in World State of war I," in Stephen Broadberry and Marking Harrison, eds. The Economics of World War I (2005) pp 310–43. online; online review

- Soule, George. The Prosperity Decade: From State of war to Depression, 1917–1929 (1947), wide economic history of decade

- Sutch, Richard. "The Fed, the Treasury, and the Liberty Bond Campaign–How William Gibbs McAdoo Won World War I." Key Banking in Historical Perspective: One Hundred Years of the Federal Reserve (2014) online; Illustrated with wartime government posters.

Race relations [edit]

- Blumenthal, Henry. "Woodrow Wilson and the Race Question." Journal of Negro History 48.1 (1963): one-21. online

- Breen, William J. "Black Women and the Slap-up State of war: Mobilization and Reform in the South." Journal of Southern History 44#3 (1978), pp. 421–440. online

- Ellis, Marker. "'Closing Ranks' and 'Seeking Honors': West. East. B. Du Bois in World War I." Journal of American History 79#1 (1992), pp. 96–124. online

- Finley, Randy. "Black Arkansans and World War One." Arkansas Historical Quarterly 49#three (1990): 249-77. doi:10.2307/40030800.

- Hemmingway, Theodore. "Prelude to Change: Black Carolinians in the War Years, 1914-1920." Journal of Negro History 65#3 (1980), pp. 212–227. online

- Hashemite kingdom of jordan, William. "'The Damnable Dilemma': African-American Accommodation and Protest during World War I." Journal of American History 82#4 (1995), pp. 1562–1583. online

- Krugler, David F. 1919, The Year of Racial Violence (Cambridge Upwards, 2014).

- Patler, Nicholas. Jim Crow and the Wilson administration: protesting federal segregation in the early on twentieth century (2007).

- Scheiber, Jane Lang, and Harry North. Scheiber. "The Wilson assistants and the wartime mobilization of blackness Americans, 1917–xviii." Labor History 10.3 (1969): 433-458.

- Smith. Shane A. "The Crisis in the Swell War: W.Due east.B. Du Bois and His Perception of African-American Participation in Earth War I," Historian seventy#2 (Summer 2008): 239–62.

- Yellin, Eric Due south. (2013). Racism in the Nation's Service. doi:10.5149/9781469607214_Yellin. ISBN9781469607207. S2CID 153118305.

Historiography and memory [edit]

- Controvich, James T. The United states in World State of war I: A Bibliographic Guide (Scarecrow, 2012) 649 pp

- Higham, Robin and Dennis E. Showalter, eds. Researching World State of war I: A Handbook. (2003). 475pp; highly detailed historiography.

- Keene, Jennifer D. "Remembering the 'Forgotten War': American Historiography on Earth War I." Historian 78#3 (2016): 439–468.

- Licursi, Kimberly J. Lamay. Remembering Globe War I in America (2018)

Primary sources and year books [edit]

- Creel, George. How We Advertised America: The First Telling of the Amazing Story of the Committee on Public Data That Carried the Gospel of Americanism to Every Corner of the World. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1920.

- George Creel Sounds Call to Unselfish National Service to Newspaper Men Editor and Publisher, Baronial 17, 1918.

- United States. Committee on Public Data. National service handbook (1917) online free

- Negro Year Book 1916

- New International Year Book 1914, Comprehensive coverage of national and state affairs, 913pp

- New International Year Volume 1915, Comprehensive coverage of national and state affairs, 791pp

- New International Year Book 1916 (1917), Comprehensive coverage of national and state affairs, 938pp

- New International Twelvemonth Volume 1917 (1918), Comprehensive coverage of national and country diplomacy, 904 pp

- New International Twelvemonth Book 1918 (1919), Comprehensive coverage of national and state diplomacy, 904 pp

- New International Year Book 1919 (1920), Comprehensive coverage of national and state affairs, 744pp

- New International Year Book 1920 (1921), Comprehensive coverage of national and land affairs, 844 pp

- New International Year Volume 1921 (1922), Comprehensive coverage of national and state affairs, 848 pp

External links [edit]

- Keene, Jennifer D.: United States of America, in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the Start World War.

- Ford, Nancy Gentile: Civilian and Military Power (USA), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Jensen, Kimberly: Women's Mobilization for War (U.s.), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Strauss, Lon: Social Disharmonize and Control, Protest and Repression (USA), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the Start Globe War.

- Taillon, Paul Michel: Labour Movements, Trade Unions and Strikes (United states), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the Kickoff Earth War.

- Little, Branden: Making Sense of the War (USA), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World State of war.

- Miller, Alisa: Press/Journalism (USA), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- Wells, Robert A.: Propaganda at Home (The states), in: 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the Kickoff World War.

- Home front end of Connecticut in World War I

- N Carolinians and the Great War: Introduction to the Home Front end

How Did Native Americans' Service In World War I Impact Their Lives On The Homefront,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_home_front_during_World_War_I

Posted by: matthiesaltrove88.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Did Native Americans' Service In World War I Impact Their Lives On The Homefront"

Post a Comment